Manual osteopathy is an allied health profession that is gaining an increasing profile around the world. The Osteopathic International Alliance (OIA) has official relations status with the World Health Organisation. Moreover, manual osteopaths all over the world will get to celebrate World Osteopathy Day on 22nd June, the day that osteopathy was originally founded in 1874 by Dr Andrew Taylor Still.

7 Highly Recommended Manual Osteopathy Treatments to Fight Chronic Pain and Many Other Conditions.

Saturday, 24 November 2018

Why I Chose Manual Osteopathy As A Profession

Manual osteopathy can make a real difference to people and their quality of life. This is because many health conditions and other movement related pain can be effectively treated with manual osteopathy. With varying degrees of success, osteopathic manual treatments can address diverse problems such as asthma, bronchitis, stomach problems, angina pain, sciatica, ear infections, and menstrual problems. In fact, manual osteopathy is highly effective in helping people who suffers from chronic pain. Whatever are their reasons for turning to an osteopath, patients often find that their overall health improves.

An important aspect of manual osteopathy is the philosophy of osteopathic holistic approach in patient care. Manual osteopaths treat the patient as an individual and not just the injury or condition. Manual osteopaths spend time to know their patients so that they can understand their unique set of circumstances and other factors which may be playing a part in their conditions. Manual osteopaths then use this knowledge to deliver a sound treatment plan in partnership with the patient.

The job prospects for manual osteopathy graduates are impressively high. Manual osteopathy provides students with practical skills which will always be in demand. Many receive job offers before they even graduate, while others choose to set up in business on their own or with fellow graduates. Manual osteopaths have great earning potential and what they can earn is largely dependent on where and how often they want to work, how many patients they want to see, what patients they want to see, and what rates they decide to charge. Besides, qualified manual osteopaths can also practice in countries all over the world, subject to local regulations.

While many manual osteopaths work with a wide variety of patients, some may choose to specialize in a niche market. Specialists in manual osteopathy can focus on work with young patients, elderly people, professional athletes, patients with specific chronic conditions or even animals. The career of an manual osteopath can evolve with time and change direction with their interests.

Manual osteopathy is a noble profession, and therefore those who pursue it are well respected and valued members of society. Like other healthcare professions, manual osteopaths must be registered with the profession's regulatory body. Manual osteopaths need to undertake regular professional development and comply with professional standards, so that the general public can have confidence in the treatment they provide.

Conditions That May Benefit From Manual Osteopathy

Many patients seek osteopathic care for aches, pains, strains, sprains, headaches, and other common musculoskeletal problems.

Nonetheless, many health problems can be and have also been successfully addressed with osteopathic manipulation. Studies have shown positive effects with the following conditions:

² Arthritis

² Asthma

² Autism

² Back pain

² Bell's palsy

² Chronic pain

² Degenerative disc and joint disease

² Ear infections

² Epilepsy

² Fibromyalgia

² Headaches

² Head Trauma and Concussions

² Irritable Bowel Syndrome

|

² Migraines

² Motor vehicle accident injury

² Neck pain

² Pregnancy and childbirth

² Reflux

² Repetitive occupational strains

² Shoulder conditions

² Sports injures

² Tendonitis

² Temporomandibular Disorders

² Physical Trauma

² Postural conditions

² Post surgical conditions

|

Benefits of Manual Osteopathy

The common benefits of manual osteopathic treatments are:

² Promote deep breathing

² Improve posture

² Improve circulation

² Enhance skin health

² Increase joint mobility

² Induce a calm mind

² Reduce anxiety

² Increase self awareness

|

² Promote mental alertness

² Increase peace of mind

² Fulfill need for human touch

² Prevent injury

² Acute and chronic pain relief

² Improve sports performance

² Decrease muscle tension

² Decrease muscle spasm

|

Manual Osteopathy: Cranial Osteopathy

Manual osteopathy in the cranial field was pioneered by William Sutherland (1873 to 1954) and remains one of the more controversial areas of manual osteopathy. Cranial osteopathy is based on the supposition that oscillatory motions of the cranial bones and sacrum exist. It stresses the importance of movement within the 29 bones of the skull; the rhythmic movement of spinal fluid through the brain, central nervous system, and body tissues; and the ability of the sacrum to move in a coordinated manner with everything else. These movements are barely perceptible and are mediated through the tension of the various dural membranes such as the falx cerebri, tentorum cerebelli, and the dura along the entire spinal cord. Their amplitude and rate are thought to provide information about the patient's health and are thought to be influenced by the application of gentle pressure over specific areas of the cranium and sacrum. Cranial osteopathy is also thought to influence parasympathetic tone because the origins of parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system are located in the craniosacral regions.

The goals of cranial osteopathy are to normalize nerve function, eliminate circulatory stasis, normalize cerebrospinal fluid fluctuation, release membranous tension, correct cranial articular strains, and modify gross structural patterns. Cranial osteopathy requires special training and should be performed only by certified practitioners. This technique is contraindicated for patients with recent trauma, a lack of biomechanical dysfunction or an aversion to receiving treatment.

Manual Osteopathy: Lymphatic Treatment

Most manual osteopathy treatments have an effect on lymphatic circulation. All lymphatic techniques begin with treatment of somatic dysfunction in areas known as “choke points.” The choke points, when dysfunctional, are areas that can obstruct the flow of lymph between body compartments. Choke points are usually treated with myofascial release techniques assisted by respiration. Once the obstruction is reduced, other lymphatic pump techniques are used to promote fluid movement, such as pectoral traction, postural drainage, effleurage, thoracic expansion, and rhythmic passive dorsiflexion of the feet. The goal is to enhance lymphatic return either by influencing negative intrathoracic pressure or mechanically assisting return of lymph from the lower extremities. As somatic dysfunction resolves, the body’s natural homeostatic mechanisms are restored and lymphatic drainage is naturally enhanced. Lymphatic treatments remove obstructions to lymphatic flow and augment the clearance of lymph and other immune elements from specific congested tissues. Lymphatic techniques are contraindicated in the presence of metastatic cancer, certain infections (e.g., tuberculosis), and hypercoagulable states.

Manual Osteopathy: Myofascial Release (MFR)

Myofascial release (MFR) is a technique that focuses on fascia and the surrounding muscles. It is similar to deep massage, but the hands of the practitioner are not merely slid along the skin surface. The goal is to stretch muscles and fascia to reduce tension. Myofascial techniques can also be adapted to promote venous and lymphatic drainage.

In myofascial release treatment, the manual osteopath applies compression or distraction forces to the area of myofascial strain, using palpatory feedback to guide the strain to resolution. Myofascial release techniques either directly or indirectly engage restrictive barriers depending on the manual osteopath’s perceived response of the fascia to palpation. The effectiveness of myofascial techniques is explained via the concept of tensegrity. A tensegrity structure consists of multiple, non-touching rods balanced by a continuous tension system. If there is problem in one component, the entire structure is affected. Applying this concept to the human body suggests that bones are the rods and the continuous tension system is the myofascial and ligamentous tissues of the body. Therefore, myofascial strain theoretically has influences across the entire body and resolution allows the restoration of a more balanced homeostatic equilibrium.

The use of myofascial release depends on the safe introduction of motion upon dysfunctional tissue. Consequently, myofascial release is contraindicated for patients with open wounds, fractures, recent surgery, deep vein thromboses, an underlying neoplasm, or other internal injuries.

In myofascial release treatment, the manual osteopath applies compression or distraction forces to the area of myofascial strain, using palpatory feedback to guide the strain to resolution. Myofascial release techniques either directly or indirectly engage restrictive barriers depending on the manual osteopath’s perceived response of the fascia to palpation. The effectiveness of myofascial techniques is explained via the concept of tensegrity. A tensegrity structure consists of multiple, non-touching rods balanced by a continuous tension system. If there is problem in one component, the entire structure is affected. Applying this concept to the human body suggests that bones are the rods and the continuous tension system is the myofascial and ligamentous tissues of the body. Therefore, myofascial strain theoretically has influences across the entire body and resolution allows the restoration of a more balanced homeostatic equilibrium.

The use of myofascial release depends on the safe introduction of motion upon dysfunctional tissue. Consequently, myofascial release is contraindicated for patients with open wounds, fractures, recent surgery, deep vein thromboses, an underlying neoplasm, or other internal injuries.

Manual Osteopathy: Counterstrain

Treatment using counterstrain is directed at discrete areas of tender tissue called tender points. Tender points are painful to the touch and they can be found in acute and chronic conditions and may be the primary indicator of somatic dysfunction or appear secondary to another medical cause. Tender points are theorized to arise from an antagonist muscle in a state of “panic,” lengthening in response to a strained and painful agonist muscle.

Counterstrain is an indirect, passive technique in which the patient is positioned away from a restrictive barrier of motion. When performing counterstrain, the manual osteopath places the symptomatic joint in the position of least discomfort while at the same time monitoring the degree of tenderness at a nearby tender point. This position of minimal discomfort is usually a position where the muscle is at its shortest length. The position is held for 90 seconds and the joint is slowly and passively returned to the neutral position. By placing the body into a position of maximal ease and comfort, the somatic dysfunction of the strained muscle should begin to resolve. Treatment is repeated until a 70-percent reduction in tenderness is reported by the patient.

The prolonged contracted state of a muscle causes shortening of both the intrafusal (muscle spindle) and extrafusal fibers. The gamma motor neurons then increase their firing rate to maintain tone in the muscle, and the muscle spindle fibers become hypersensitive. If the hypersensitive muscle is now lengthened too rapidly, a reflex overstimulation of the alpha motor neurons will occur. This sensory input travels to the higher centers of the central nervous system, which may misinterpret this input and respond with excessive gamma motor stimulation, maintaining the spasm. Reshortening the muscle by using counterstrain technique allows the muscle spindle to shorten and resume normal firing. The central nervous system then resets its gamma motor neurons after about 90 seconds. Absolute contraindications for counterstrain occur in patients with fractures or torn tendons in areas of dysfunction.

Counterstrain is an indirect, passive technique in which the patient is positioned away from a restrictive barrier of motion. When performing counterstrain, the manual osteopath places the symptomatic joint in the position of least discomfort while at the same time monitoring the degree of tenderness at a nearby tender point. This position of minimal discomfort is usually a position where the muscle is at its shortest length. The position is held for 90 seconds and the joint is slowly and passively returned to the neutral position. By placing the body into a position of maximal ease and comfort, the somatic dysfunction of the strained muscle should begin to resolve. Treatment is repeated until a 70-percent reduction in tenderness is reported by the patient.

The prolonged contracted state of a muscle causes shortening of both the intrafusal (muscle spindle) and extrafusal fibers. The gamma motor neurons then increase their firing rate to maintain tone in the muscle, and the muscle spindle fibers become hypersensitive. If the hypersensitive muscle is now lengthened too rapidly, a reflex overstimulation of the alpha motor neurons will occur. This sensory input travels to the higher centers of the central nervous system, which may misinterpret this input and respond with excessive gamma motor stimulation, maintaining the spasm. Reshortening the muscle by using counterstrain technique allows the muscle spindle to shorten and resume normal firing. The central nervous system then resets its gamma motor neurons after about 90 seconds. Absolute contraindications for counterstrain occur in patients with fractures or torn tendons in areas of dysfunction.

Manual Osteopathy: Osteoarticular Treatment

Osteoarticular treatment in manual osteopathy is a set of low-velocity and high-amplitude techniques which involve the application of gentle and repetitive motions on to the joints of the body to restore mobility in a restricted joint. Manual osteopaths use this treatment to reduce muscle spasms around a joint, reduce neurological irritations near a joint, normalize the mobility of a joint, and to eliminate pain and discomfort. The osteoarticular technique usually involves the gentle movement of 2 joint surfaces. Before treatment, the manual osteopath will carefully place the patient into an optimal position that will reduce the energy and force required to perform the technique. It is not necessary to perform the techniques at the anatomical end range of movement of the joint. Therefore, many patients find that osteoarticular techniques are more comfortable than conventional joint manipulations. The beneficial effects of osteoarticular techniques are proven in clinical trials. The evidence for the effectiveness of osteopathic osteoarticular techniques suggests that the central nervous system is involved in mediating the endogenous pain inhibition system. Osteoarticular treatment is contraindicated in patients with fractures, unstable joints, and recent surgery.

Manual Osteopathy: Muscle Energy Technique (MET)

One cause of somatic dysfunction is postulated to derive from chronically contracted muscles which affect the body’s normal range of movement. Muscle energy is a direct, active treatment with broad applications to any part of the body restricted in motion. In treatment, the manual osteopath engages the restrictive barrier and asks the patient to voluntarily move from a precisely controlled position. The osteopath exerts an equal and opposite force to the patient's active force from a certain position and in a specific direction. During the patient’s effort, the physician provides an isometric counterforce for 3 to 5 seconds and then allows the muscle to relax for 3 to 5 seconds. A new restrictive barrier is then engaged and the process is repeated 2 to 4 times. The result is repeated isometric contractions with passive range of motion through the barrier after each isometric contraction.

The goal of muscle energy technique is to increase joint mobilization and increase the length of contracted muscles. Because no thrusting is done, this procedure has a very low likelihood of producing complications and can be used where HVLA technique is contraindicated. The mechanism of action of muscle energy is thought to be related to the reciprocal inhibition of agonist/antagonist muscles and the Golgi tendon reflex. When a stretch reflex excites one muscle, reciprocal innervation causes simultaneous inhibition of the antagonist muscle. The Golgi tendon organ reflex is an inhibitory reflex that can cause relaxation of a muscle when excessive tension is placed on the Golgi tendon organ through either stretching or contracting the muscle. Muscle energy is contraindicated in patients with low vitality, fractures, unstable joints, and recent surgery.

Osteopathic Manual Treatment: High Velocity Low Amplitude (HVLA)

The HVLA technique (also known as mobilization with impulse) is a direct, active technique in which the physician engages the pathological barrier of a joint restricted in a normal plane of movement. Once a restricted “barrier” is engaged, the physician employs a quick thrust over a short distance through the inhibited plane of motion. The movement is within a joint's normal range of motion and does not exceed the anatomic barrier or range of motion. With proper positioning of the patient, HVLA technique requires very little force and can be targeted to specific spinal segments. The goal of the treatment is to restore normal joint play or a desirable gap between articulating surfaces that permits free translational or gliding motion in addition to the usual angular motion. This is achieved by directly engaging the restrictive component of a joint’s somatic dysfunction. Of all the osteopathic techniques, HVLA technique most closely resembles the chiropractic technique and has the greatest number of contraindications. Contraindications include rheumatoid arthritic involvement of the cervical spine, carotid or vertebrobasilar vascular disease, the presence or possibility of bony metastasis or severe osteopenia, and a history of pathological fractures.

Osteopathic Manual Treatment (OMT)

Osteopathic manual treatment (OMT), also known as osteopathic manipulative treatment, is a set of hands-on techniques used in osteopathic medicine to diagnose, treat, and prevent illness or injury. OMT provides manual adjustments to the musculoskeletal system that modulates the autonomic nervous system by reducing sympathetic tone and, to a lesser degree, augmenting parasympathetic effects.

Osteopathic manual practitioners use different OMT techniques alone or in combination to resolve somatic dysfunction. Treatments are either “direct,” in which the physician engages a patient’s restricted plane of motion, or “indirect,” in which the body is placed into a position of ease during treatment. OMT requiring a therapeutic correcting force is called an “active” treatment when provided by the physician and “passive” when provided by the patient. These techniques are normally employed together with therapeutic exercise, dietary, and occupational advice in an attempt to help patients recover from pain, disease and injury.

Osteopathic manipulative treatment consists of over many different techniques or procedures. They are broadly grouped into 7 major types: high-velocity-low-amplitude (also called thrust or mobilization with impulse), muscle energy, osteoarticular, counterstrain, myofascial release, lymphatic pump techniques and cranial osteopathy.

Manual Osteopathy and Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is pain that lasts more than 3 months or past the time of normal healing, therefore emphasizing the transition from acute injury pain to a persistent chronic pain syndrome. Changes in the peripheral and central nervous system and biopsychosocial factors perpetuate chronic pain. Often occurring after musculoskeletal damage and healing, chronic pain is a redundant signal that serves no biologically useful purpose. Over time, chronic pain can set in motion a self-perpetuating chronic pain syndrome.

Chronic pain syndrome is closely linked to somatic dysfunction. Although structure and function issues may trigger the initial report of pain, homeostatic dysfunctions and the disruption of autonomic nervous system may worsen and perpetuate pain perception and distress. Moreover, emotions are often linked to musculoskeletal sensations, thus further dysregulating immune, neurologic, and endocrine systems. This breakdown in homeostasis is seen psychologically as pain-related fear, depression, anxiety, and decreased quality of life. Chronic pain eventually causes brain and nervous system reorganization and self perpetuating neural activity.

According to osteopathic philosophy, chronic pain can upset the biopsychosocial balance. Chronic pain is often maintained by noxious sensory input originating in the musculoskeletal system, making it a prime target for osteopathic interventions. In addition, chronic pain creates a sustained autonomic nervous system arousal, elevated cortisol levels, and a prolonged “fight or flight” response. Patients can eventually become exhausted and present symptoms of depression, insomnia, fatigue, guarding muscles, and fear of movement.

Manual osteopathy can be recommended as an option for the management of chronic pain. Physical examination is normally focused on somatic dysfunction, the biological pain generator, and what can be done to help the patient. The effectiveness of manual osteopathy for treating chronic pain is validated by clinical research.

In fact, the largest and most rigorous randomized controlled trial on osteopathic manual treatment (OMT), the OSTEOPAThic Health outcomes In Chronic low back pain Trial, was published in 2013. It used a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, 2 × 2 factorial design to study OMT for patients with chronic low back pain (LBP). A total of 455 participants were divided into 2 categories: those who reported low baseline pain severity (<50 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale; 269 participants [59%]) and those who reported high baseline pain severity (⩾50 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale; 186 participants [41%]). Six 15-minute OMT sessions were provided every 2 weeks by the same trained osteopathic physician over 8 weeks. Outcomes were assessed at week 12. The provided OMT techniques included high-velocity, low-amplitude; osteoarticulatory; soft tissue; myofascial stretching and release; strain-counterstrain; and muscle energy. Sham OMT included active and passive range of motion, light touch, improper patient positioning, purposely misdirected movements, and diminished force.

The study revealed a large effect size for OMT vs sham OMT in providing substantial low back pain improvement in patients with high baseline pain severity. Clinically important improvement in back-specific functioning was also found in the OMT group compared with that in the sham OMT group. The findings of this study suggest that OMT could be an excellent adjunct to the care of patients with severe chronic LBP.

Manual Osteopathy and Somatic Dysfunction

Somatic dysfunction, or ‘osteopathic lesion’, has been considered a central concept of the theory and practice of osteopathy for over a hundred years. The term represents a single clinical entity that is diagnosed exclusively by osteopaths, and it can impact function, general health, and predisposes the body to disease. It is proposed to be a reversible, functional disturbance, which can be specifically and appropriately addressed using osteopathic manual treatment (OMT). Somatic dysfunction may be encountered in a variety of medical conditions, including musculoskeletal disorders and systemic diseases, that are managed by manual osteopaths.

Somatic dysfunction has been defined as ‘impaired or altered function of related components of the somatic (body framework) system: skeletal, arthrodial, and myofascial structures, and related vascular, lymphatic, and neural elements.’ The term can be used broadly to refer to dysfunction of a group of tissues or a region, or used more specifically for dysfunction of a single body part.

Somatic dysfunction is not synonymous with spinal pain, and palpable signs of dysfunction may be detected in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. It has been proposed that the presence of somatic dysfunction in asymptomatic individuals can create biomechanical and neurological disturbances which predispose the individual to further pain and other health complaints.

Somatic dysfunction can be detected by palpation using four cardinal clinical signs: tenderness, asymmetry, range of motion abnormality, and texture changes of body tissues. The mnemonic TART or ARTT is commonly used as a memory aid for these clinical signs. At least two of these signs must be present for a diagnosis of somatic dysfunction. Most osteopaths also consider motion restriction an important feature of somatic dysfunction.

Somatic dysfunction is likely caused by tissue injury and degenerative changes. Tissue factors may include either macro-trauma or repetitive micro-trauma of the joint capsule, periarticular soft tissues, or annulus of the disc, and this can lead to inflammation and activation of nociceptors (pain receptors). Nociceptive-driven functional changes may further produce alterations in tissue texture and pain sensitivity, two of the cardinal features attributed to somatic dysfunction by osteopaths. Additionally, degenerative changes will also contribute to tissue texture and range of motion changes and to activation of nociceptive pathways.

Somatic dysfunction is commonly described as being acute or chronic, and these stages likely relate to acute tissue inflammation or long-term degenerative change, with both potentially accompanied by neurological and functional changes. In the acute stage, tenderness is most easily explained by nociceptor activation and peripheral sensitisation following tissue injury. In the chronic term, nociceptive-driven neuroplastic changes in the dorsal horn and higher central nervous system can lead to long term pain and tenderness.

In summary, the osteopathic concept of somatic dysfunction is based on biomedical and biomechanical models, where physical clinical findings represent a functional abnormality and subsequent manipulative treatment restores the function. The structural assessment findings associated with somatic dysfunction represents a fundamental and uniquely osteopathic approach to clinical practice. Such findings can guide osteopathic manual treatment (OMT), which is the therapeutic application of manually guided forces to improve physiological function and to restore homeostasis that has been altered by somatic dysfunction.

American Style Osteopathy vs European Style Osteopathy

In North America, the term “osteopathy” refers to American style osteopathic practice that consists of manual therapy, surgery and prescription of medications. This type of “osteopathy” is provided only in USA. Those who practice American style osteopathy (osteopathic medicine) are called osteopaths or osteopathic physicians, and those who provide manual treatment are called osteopathic manual practitioners.

Outside USA, the term “osteopathy” refers to a profession that provides only manual therapy, without performing surgery or prescribing medications. In Canada other terms such as “European style osteopathy” and “manual osteopathy” are also used to describe those who provide osteopathic manual treatment. The only exception is the province of Quebec in Canada where manual osteopaths are permitted to use the title "osteopath".

In all other countries outside North America, both American style osteopaths (osteopathic physicians) and European style osteopaths (osteopathic manual practitioners) are called osteopaths.

In summary, European style osteopathic manual practitioners do not prescribe medications or perform surgery. American style osteopaths (also known as osteopathic physicians) perform surgery, prescribe medications, and use osteopathic techniques to manage the condition of patients.

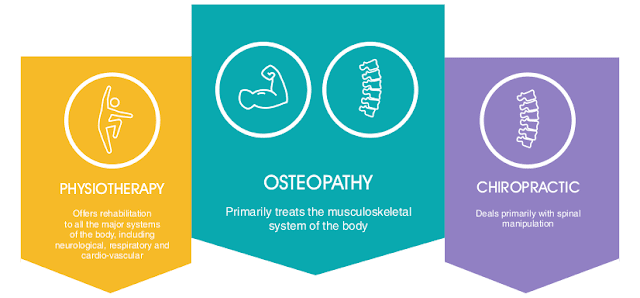

Osteopathy vs Chiropractic vs Physiotherapy?

Manual osteopathy is not the same as chiropractic or physiotherapy. The osteopathic manual practitioner mainly treats the musculoskeletal system of the body by restoring the normal working relationship between body structure and function. The chiropractor addresses musculoskeletal problems mainly with joint and spinal manipulation. The physiotherapist does not only treat the musculoskeletal system, but also provides rehabilitation therapy to the other major systems of the body, and these include the neurological, cardiovascular, and cardiopulmonary systems. Whereas chiropractors and physiotherapists use manual medicine to address problems that are primarily limited to the musculoskeletal system, osteopathic teaching posits that osteopathic manual treatment has a distinct effect beyond the musculoskeletal system.

Manual osteopathy takes into account not only the physical symptoms, but also the patient’s lifestyle and attitudes, as well as his or her overall health, thus effectively treating the patient as a whole. The manual osteopath considers physical, environmental and stress factors simultaneously, whereas the general medical practitioner would usually address these factors individually and in isolation from each other.

Manual osteopathy takes into account not only the physical symptoms, but also the patient’s lifestyle and attitudes, as well as his or her overall health, thus effectively treating the patient as a whole. The manual osteopath considers physical, environmental and stress factors simultaneously, whereas the general medical practitioner would usually address these factors individually and in isolation from each other.

Founder of Osteopathy : Andrew Taylor Still

Andrew Taylor Still, an American medical doctor and surgeon, founded osteopathy in 1874. The son of a Methodist minister, Still attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Kansas City, served as a state legislator, and enlisted in the Ninth Kansas Cavalry and attained the rank of major during the Civil War. After the war, Still provided health care to settlers and American Indians. As he faced the epidemics of his time such as cholera, pneumonia, smallpox, diphtheria, and tuberculosis, he became increasingly disenchanted with orthodox medicine. In the search for adjuncts or substitutes for many prevailing medical therapies, he eschewed the liberal use of pharmaceutical drugs.

Still believed that the primary role of the physician was to facilitate the body's inherent ability to heal itself. He also believed that the structure and function of the body were closely related and that problems in one organ affected other parts of the body. He maintained that the physician could best promote health by ensuring that the musculoskeletal system was in as perfect alignment as possible and obstructions to blood and lymph flow were minimized or eliminated. To that end, Still developed various manipulative techniques and a philosophy of medicine that aimed to improve the prevailing system of medicine of his time.

The state of medical practice in the 19th century was characterized by multiple schools of healing, many of dubious value, and physicians who were often poorly or inadequately trained. Treatments such as bloodletting and the use of purgatives, mercury, or alcohol-based compounds were frequently seen. The American Medical Association was the dominant medical organization of the time. In trying to establish order and improve quality, the American Medical Association had little tolerance for other schools of thought.

Still's ideas were initially rejected by his peers, and this initiated a half century long struggle for acceptance. Ostracized by both medical and societal organizations, Still was compelled to become an itinerant physician in Kansas and Missouri. However, his efforts to improve circulation and correct altered body mechanics through the use of manual medicine became more successful. Increasing demand for his services led to the establishment of the first osteopathic medical school, the American School of Osteopathy, which opened in Missouri in 1892. The curricula emphasized anatomy, histology, physiology, toxicology, and manipulation.

According to the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, "Osteopathic medicine is a distinctive form of medical care founded on the philosophy that all body systems are interrelated and dependent upon one another for good health." In the western world, Dr Still is widely considered as the first physician to treat each patient as a whole, while searching for the cause of dysfunction rather than treating the symptoms.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)